James Joyce once famously said that the best way to write an anti-war novel is to not write a novel about war. In the years since I first read that little piece of wisdom, I've gone round and round a few times in terms of whether I agree or not. In the end, I think it's an insoluble question -- when we engage artistically and aesthetically with the issue of warfare, there is always an extent to which the material must embrace its subject matter, must lose a certain amount of critical distance and hazard becoming in some small part a glorification. I think this was Joyce's principal insight, something echoed by the great film auteur Francois Truffaut, who maintained that there can never be any such thing as an anti-war film because the medium inevitably turns it into a thrilling spectacle.

James Joyce once famously said that the best way to write an anti-war novel is to not write a novel about war. In the years since I first read that little piece of wisdom, I've gone round and round a few times in terms of whether I agree or not. In the end, I think it's an insoluble question -- when we engage artistically and aesthetically with the issue of warfare, there is always an extent to which the material must embrace its subject matter, must lose a certain amount of critical distance and hazard becoming in some small part a glorification. I think this was Joyce's principal insight, something echoed by the great film auteur Francois Truffaut, who maintained that there can never be any such thing as an anti-war film because the medium inevitably turns it into a thrilling spectacle.At the same time, art offers the most powerful and poingant critiques of war, critiques whose rhetorical force vastly eclipses the academic or journalistic, which can so easily stray into pedantry. Who recovers quickly from the gut-shots of such novels as Mailer's The Naked and the Dead, Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms or Heller's Catch-22? or films like Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket or A Bridge Too Far? paintings like Picasso's Guernica? poetry like that of Wilfred Owen? And yet each in its own way aetheticizes warfare, or else (as in Catch-22) renders it as an experience so absurd as to pull the teeth of its own critique.

I'm pondering this today for a variety of reasons:

- It's Remembrance Day

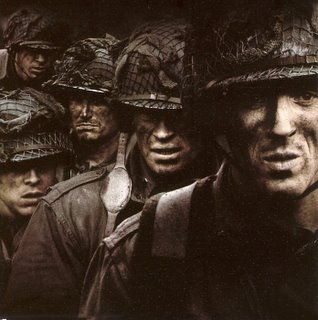

- I've been watching the HBO series Band of Brothers

- An article in the most recent Harper's Magazine has put me into this head space

- Mulling over these heavy questions is vastly preferable to grading essays

else HBO has done, is truly remarkable -- the more so because (from what I'm gleaning) has no pro- or anti-war agenda. It is really just about the experiences of a specific company of soldiers from Normandy onward, and does an extraordinary job of rendering what I imagine things were actually like (this of course being the sticking point -- I can only imagine). I find it slightly ironic that the series was produced by Tom Hanks and Stephen Spielberg; it is everything that Saving Private Ryan tried, and failed, to be. If ever there was a film trying desperately to be anti-war that ended up becoming a cliched glorification, that was it.

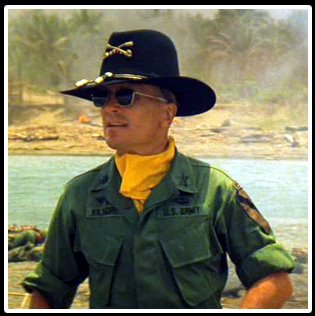

else HBO has done, is truly remarkable -- the more so because (from what I'm gleaning) has no pro- or anti-war agenda. It is really just about the experiences of a specific company of soldiers from Normandy onward, and does an extraordinary job of rendering what I imagine things were actually like (this of course being the sticking point -- I can only imagine). I find it slightly ironic that the series was produced by Tom Hanks and Stephen Spielberg; it is everything that Saving Private Ryan tried, and failed, to be. If ever there was a film trying desperately to be anti-war that ended up becoming a cliched glorification, that was it. The Harper's article I'm referring to is titled "Valkyries over Iraq" is sort of an extended review of the film Jarhead, something I'd had no interest whatsoever in seeing, but now am keen to do so (for a very intelligent and thoughtful consideration of the film, see Mister Eano's comments here). The film is based on the memoir by Anthony Swofford, a marine sniper who saw action in the original Desert Storm; the Harper's article focuses on a particular scene in which marines are riled up to a bloodthirsty fervour by being shown war movies -- and the movie in question is Apocalypse Now; the scene depicted is the infamous "Ride of the Valkyries" raid by Robert Duvall's airborne cavalry on a village at the Mekong Delta so the film's main characters can begin their journey upriver.

The Harper's article I'm referring to is titled "Valkyries over Iraq" is sort of an extended review of the film Jarhead, something I'd had no interest whatsoever in seeing, but now am keen to do so (for a very intelligent and thoughtful consideration of the film, see Mister Eano's comments here). The film is based on the memoir by Anthony Swofford, a marine sniper who saw action in the original Desert Storm; the Harper's article focuses on a particular scene in which marines are riled up to a bloodthirsty fervour by being shown war movies -- and the movie in question is Apocalypse Now; the scene depicted is the infamous "Ride of the Valkyries" raid by Robert Duvall's airborne cavalry on a village at the Mekong Delta so the film's main characters can begin their journey upriver.As the article points out, Apocalypse Now is eminently an anti-war film: yet here a movie theatre full of marines, all intimately familiar with the sequence, shout in enthusiasm, speak the lines in unision with the film, and generally get entirely juiced by the depictions of violence meant to give audiences a sober consideration of war's horror.

The thing is, the scene is pretty thrilling -- not so much because of the violence, but because it's a piece of first-rate filmmaking. The very genius of the sequence is to inspire a certain engagement ... it really wouldn't work otherwise, and to a certain portion of the audience, our satisfaction and empathy is the most horrifying thing about it. We can't help liking Robert Duvall's psychotic colonel, and somewhere in ourselves agreeing that we love the smell of napalm in the morning.

But of course, here is the problem with aestheticizing war (or anything, for that matter): nuance only works for some. Which is not to make a simplistic division between "smart" and "stupid" audiences -- we all have our own idiosyncratic buttons, and that which pushes those buttons and inspires a certain reaction in me will do something entirely different for someone else. No, what I mean is that any engagement with something emotionally charged one way or another poses dangers for the artist in that if one wishes to approach something truthfully there is, necessarily, the need to embrace it. The world is full of bad art that is pedantic. Really, that should be left to professors like me.

But all this is central to the whole issue of remembrance, too ... how do we pay homage to our veterans while abhorring war? It's questions like this that make me understand the appeal of conservatism: if war is invariably a valid option, there's no concern here. Unfortunately I cannot quite separate myself from my liberalism, nor can I embrace the other militant side of the equation that tars all militarism with the same brush. Hence, I found myself in a strange emotional situation about a week ago ...

I got the poppy I've been wearing this past week from a very frail-looking elderly veteran sitting at a card table outside the liquor store near campus. He was in his dress uniform with a myriad of honours pinned to his chest, reading a paper, and looking (to my overly sentimental mind) rather lonely. And so very very old and tired. It occurred to me there that we will very soon no longer have any living witnesses to this century's two world wars, no more actual people to remind us of those momentous, excruciating and tragic events, and our collective memory will be relying on archives, history books and (sigh) Hollywood.

I'm not given to weepiness, but I found myself actually fighting back tears. I dropped a ten-dollar bill in the donation box, which prompted a pleased and surprised "Thank you" from the veteran. I wanted to say, "No, thank you," but I didn't actually trust myself to respond, so just nodded, pinned on the poppy, and left.

It was a very odd moment. While being an avid consumer of war movies, novels and history books, I'm hardly a pro-military aggression person. Quite the opposite: in so very many ways I am the stereotype of the anti-war milquetoast lefty liberal. I abhor what's currently happening in Iraq; I was pleased beyond words that our Prime Waffler kept us out of that war; and I adhere to the quaint notion that wealthy nations with advanced and powerful militaries are morally obligated to lead with the olive branch, even when that entails suffering at the hands of a lesser force. My fascination with representations and histories of war in fact has much to do with not really getting it, not understanding the drive to aggression. I watch and read and study in the hopes of understanding. That, and there's the added fascination that comes with instinctively knowing I would be a thoroughly crappy soldier.

At the same time, I am immensely proud of my country's military history. Little known fact: we have the third best-trained military in the world, just behind Israel and Switzerland. And so on Remembrance Day I always make a point of paying tribute to our soldiers, particularly considering that my little brother was one for a while.

At the same time, I am immensely proud of my country's military history. Little known fact: we have the third best-trained military in the world, just behind Israel and Switzerland. And so on Remembrance Day I always make a point of paying tribute to our soldiers, particularly considering that my little brother was one for a while.I have at times be given grief over this by leftier or pacifist acquaintances, who have considered this mere glorification ... who have believed that straightforward denunciation of militarism in all its incarnations is the only acceptable moral stance -- ergo, wearing a poppy in tacit support of both veterans and active soldiers is the equivalent of celebrating violence and warfare.

Suffice it to say, I consider this mere idiocy -- simplistic, reductive idiocy that is the flip side of unthinking jingoism. And worse, it's lazy thinking. Not even Noam Chomsky buys that line of thinking.

It is in fact Chomsky that made what is, for me, the most critical distinction between systemic militarism and individual action: namely, that the individual soldier's behaviour on the battlefield has more to do with the general philosophy or lack thereof informing those at the helm of the war machine. He was speaking specifically about Vietnam, saying that such tragedies as the My Lai massacre, while horrific, should be, in the morass of ambiguity about that that war was about, hardly surprising. Chomsky actually decried the practice of villifying soldiers returning from Vietnam -- arguing that while, yes, they had their own morality to answer to and should certainly not be excused for war crimes, the genuine criminals are those who prosecute such a war. And while he was talking about Vietnam, I think the events at Abu Ghraib are of a similar character; it is criminally naive to imagine that this was merely a few bad eggs acting outside any authority. There is, to my mind, a direct causal line from Donald Rumsfeld to Lynndie England. If there's a metaphor for the US presence in Iraq, Abu Ghraib would be it.

Actually, as with so many things, Shakespeare said it first. A soldier in Henry V's army warns the disguised king -- not knowing to whom he's speaking -- that if the kings cause for war "be not good, the king himself hath a heavy reckoning to make, when all those legs and arms and heads, chopped off in battle, shall join together at the latter day and cry all 'We died at such a place'."

I say all this by way of saying that, whether we agree with the motives behind a given war or not (and as far as WWII is concerned, I think that's a no-brainer); whether we abhor the violence of warfare or not; whether one believes in the need for a military or not -- I believe we have a debt of gratitude to our soldiers, active or retired, living or dead. If the cause be not good, deplore the war and those who orchestrate it, but honour those who fight it.

Wow, this was a long post. If you made it to this sentence, thanks for your tenacity. :-)

9 comments:

Je me souviens!

"Mulling over these heavy questions is vastly preferable to grading essays"

- nice quote, your name is searchable on google, go correct our essays.. you filthy ,no good, son of a bitch...

anonymous -- you probably meant to say "nice quotation"....

I hope he'll be able to track you down somehow.

How cowardly of you though...

Sad.

Well, that was interesting, and I think there are many more who feel the same. I am fortunate enough to have had a family member who fought in WW II. Unfortunately for me, I only have stories he told others to go on, since he passed away the year before I was born. From what I have gleaned from those conversations, he didn't say much about the battle. Which makes me sad. I would have liked to know more, to have heard the stories and to have seen his face when he talked about liberating a people he had no connection with other than his attendance at their war. My grandfather worked on munitions. And he lost his toenails as a result. Never again was he able to eat outside, eat processed foods, watch someone fighting over something trivial, or speak of the fear, the sounds, the sights, of that war across the ocean.

Which is why, when I watch Saving Private Ryan, I can't bear to sit through the last battle. Regardless of the "Hollywoodization" of the war or the bias of some directors when it comes to this, I find myself moved by their dramatization of various parts of the films. Because someone I loved, someone who was a part of me, walked from Windsor Ontario to London Ontario to sign up to go and liberate countries far away. And what he saw, I can only imagine. He, and many others, did this for me, for my family, for my future, for my country's future. Without hesitation, without fear, without question. They stood up for us.

Ok, whoa, that was really deep, I think it was all the big words in your post. I might actually be learning something.

Does this mean I have to pay tuition now???

How truly brave (???) of Anonymous to make such judgements without identifying his/herself. Thank heavens the future of our country didn't rest on such outstanding courage. We'd all be speaking German by now.

Nice quotation Anonymous. I am doubly sure that your essay is searchable on the Internet as well. Out of all the posts you decide to respond to you choose the Remembrance Day one. I am glad to see that you have respect for what our grandfathers and Great Grandfathers fought for. Well-done loser.

"I am doubly sure that your essay is searchable on the Internet as well." -- I actually laughed out loud. You're probably right, fanglyfish!

Anonymous: Let me profile you. After over 30 years of teaching students, I can tell who and what you are. You are a member of that fringe group of juvenile, self centred shallow, intellectually bankrupt self serving sycophants who cannot, for one moment, abide by those who truly have insight into the souls of those around them. Your self loathing translates into a hatred which, is spread amongst those who are your moral and intellectual superiors. Don't you have something better to do than google your profs on a Friday night. SLOW DATE TIME?

Post a Comment