Well,

this is worrisome. Not for us in Canada, not yet -- it's a report issued by the Secretary of Education's Commission on the Future of Higher Education, addressing the issue of high university tuitions and asking why this is so. I found this on Michael Berube's blog, and

his commentary on it is funnier and more incisive than whatever I'm about to write. Which doesn't mean I'm not going to write it, just that you should go read his first, and then come back.

To sum the report up: tuition has shot up by leaps and bounds because of (1) tenure, (2) inefficiency. Tenure actually falls under the larger inefficiency rubric, but it is emblematic of the universities' stubborn adherence to outmoded systems of adminitration, as is the practice of having faculty (“neither trained in nor committed to management”) in all the key administrative positions -- Deans, Presidents, Department Chairs, etc.

Tenure, so the report states, is particularly pernicious, not just because it creates a situation in which tenured professors are unassailable and unfireable, but because it is anathema to good business practice. How to correct this? Unsurprisingly, the report suggests relying increasingly upon limited-term contract hires and part-time instructors, which will be significantly less expensive for universities than full-time, tenure-track positions.

So let's think about this for a moment: what would a university without tenure look like?

This is what I tend to think of as the migrant-worker model. Imagine hundreds of PhDs and ABDs lining the roadside every morning while a truck with a university president in the flatbed with a megaphone cries out the daily needs and capriciously selects hungry part-time profs to fill teaching positions for the day.

OK, I exaggerate, but it is a model that slowly encroaches on all universities -- increasingly, courses are taught by part-time people who get paid by the course and contractual faculty with a one to three year contract.

Well, you ask: what is the problem with that? Shouldn't universities be subject to the same market forces as anyone else?

My answer -- which is

only partially derived from the fact that I'm four or five years away from tenure myself -- is No! in thunder.

Yes, I have a stake in the game now myself and obviously want to maintain the benefits that accompany full-time tenured employment. But there is a misconception in the popular imagination that imagines professors cease working after that magic moment ... that they earn their salaries for teaching six to nine hours a week and doing nothing more, all the while reaping the benefits of sabbaticals and grants. (At least once a year, someone -- usually Margaret Wente -- writes an op-ed column on this very subject, invariably suggesting that professors be "forced" to work forty hours a week ... which inevitably leads professors to comment dryly that they would

love to be forced to work forty hours a week -- it would cut their work-weeks by twenty hours or more).

To begin with: to use my own case as an example, I went through thirteen years of school before arriving at the point I now find myself. Five years on a BA, one on an MA, seven on a PhD. In the eight years since graduating the BA, I have seen countless friends and acquaintances get hired in solid and occasionally lucrative jobs; pay off their student loans; buy homes; etc etc. I don't begrudge them that by any stretch -- I made my choice, and lived as a student for eight years longer than was strictly necessary, all the while racking up more loans and wasting money on rent because at no point did I have the capital to buy a house. Again, not bitter about that. My point is, it's not as if I emerge from the other end of that to take on a six-figure salary. I have (almost) no complaints about my salary, but it is hardly lucrative. Even after tenure, I'm still going to be falling far short of friends and acquaintances' incomes who have been establishing themselves in their respective professions for the past eight years.

So: having been in school for thirteen years, with significant debt and no assets, it strikes me that the material trade-off is rather a disappointment. But I didn't get into this for the money -- and anyone who does is really too stupid to live. I got into this profession because I am deeply invested, philosophically and spiritually, in education, reading & writing, and the value of the intellectual in society. If I'd been interested in a high salary I'd have done law school right out of my BA.

Of course, here's the sticking-point: I'm not so altruistic to have gone through all that if there had been no prospect whatsoever of full-time employment. If the academic landscape were entirely populated with contractual jobs and part-time work, why would I put myself through all that?

Which brings me to argument #1 against the migrant-worker academy: within a generation, your ready supply of PhDs would dry up, for the precise reason I articulated above.

Argument #2? Even if there were people still keen to do PhDs, there would be no graduate programs left, for the simple reason that graduate programs by design and definition need tenured faculty to exist. How do you advise a grad student when you're on a two-year contract? How do you attract grad students to begin with without a solid and well-established roster of active and engaged professors?

Argument #3: even if we accept the demise of grad programs as they exist and radically ratchet back the standards for the hiring and accrediting of professors, undergraduate programs themselves would suffer. Why? Because of a lack of depth. We're all familiar with the stereotype of the socially inept, head-up-his-own-ass prof who is a brilliant researcher but a crappy teacher; and not a school year goes by where I don't hear someone lament the absence of some sort of set of standards in the classroom to be applied to professors (and I don't doubt that occasionally I am the object of such anger). A fair point, but in my experience that pedagocially inept professor is the exception to the rule ... more often than not, professors are quite engaged in the classroom, they want to share their ideas and research and passions with the students, and they have an investment in teaching. The point here is that I am at my best in the classroom teaching that which I know best -- I can offer my students a more nuanced, informative experience of the material when it somehow radiates from my own research and investigations. And that is something that will only get better.

Research, in other words, isn't simply about grants and excuses to travel or take sabbaticals -- it informs not just one's own teaching, but the character of a department. When teaching part-time, professors must take on a significantly higher teaching load to make ends meet; when on contract, they are similarly loaded down with an excess of courses to the extent that the job becomes a mechanical exercise in preparation and grading, with no time or energy left over for reflection and inquiry ... to say nothing of the fact that a significant number of the courses one teaches are, at best, tangential to one's own research areas (my first part-time teaching assignment? Shakespeare ... not that I don't love that topic, but as a twentieth-century Americanist, I'm not exactly the most qualified. Couple that with the fact that it was my first real teaching attempt, and I'm often tempted to send all the students in that class notes of apology).

The desire to apply business models to education, which is what essentially informs this report, is exceptionally dangerous and damaging -- just look at the education system in Ontario after ten years of Mike Harris' Common Sense Revolution, which treated grade schools and high schools with this very sort of business model. "Efficiency" was the watchword there too, and Ontario schools won't recover for years. The point of education is that it is singularly

inefficient. Why? Because it is something whose "product" is not goods and services, but people and minds. Indeed, the "product" of the modern univeristy as theorized by Immanuel Kant and Wilhelm von Humboldt was

citizens -- or more specifically, an intelligent, educated, informed and engaged citizenry. Not, you will note, "taxpayers."

Citizens. We don't hear that word much anymore, do we?

OK, I've ranted long enough. I just hope our dear prime minister doesn't read that report and start getting any ideas.

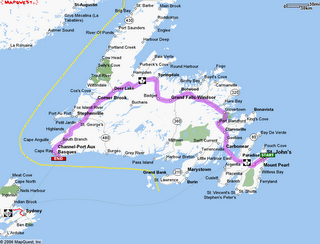

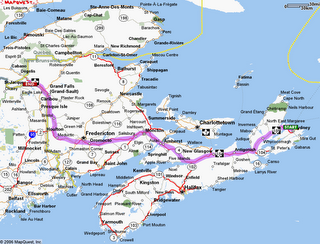

I stopped for lunch in Grand Falls-Windsor at 1:00, and spent some time driving around in search of a lunch that would be something more substantial than merely fast food. I finally stopped at a sort of skanky-looking pub called Kelly's Inn, but then I've often found that, pub-wise, a skanky exterior sometimes disguises some halfway-decent local colour.

I stopped for lunch in Grand Falls-Windsor at 1:00, and spent some time driving around in search of a lunch that would be something more substantial than merely fast food. I finally stopped at a sort of skanky-looking pub called Kelly's Inn, but then I've often found that, pub-wise, a skanky exterior sometimes disguises some halfway-decent local colour.

The fog, she do roll in quick, don't she?

The fog, she do roll in quick, don't she?